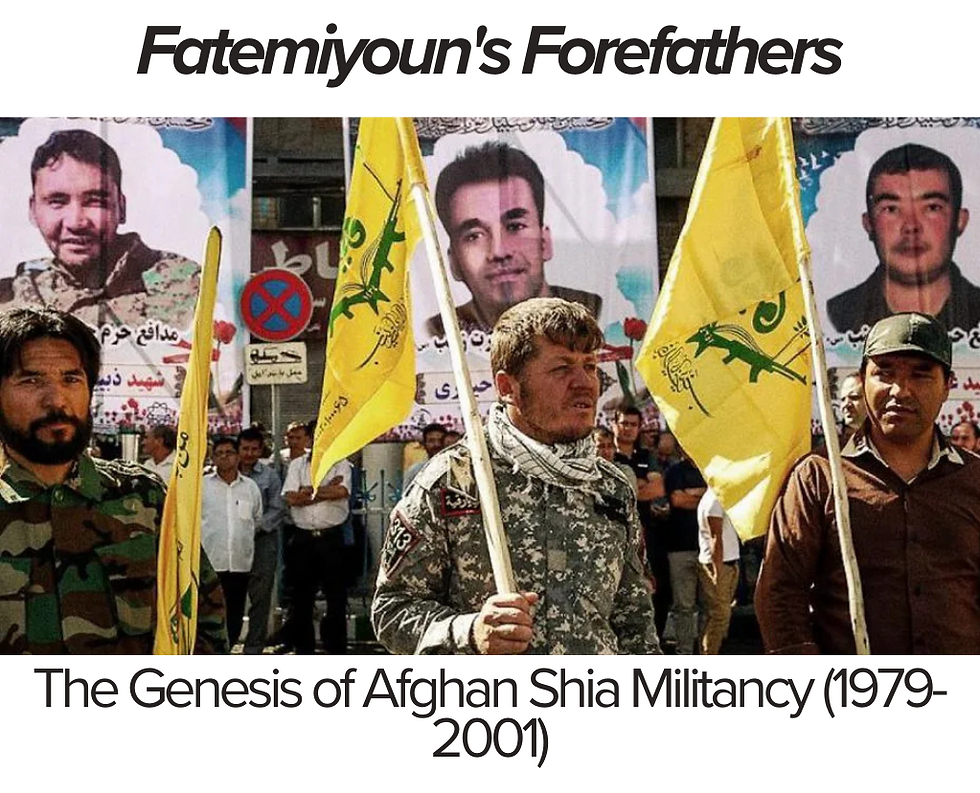

Fatemiyoun's Forefathers: The Genesis of Afghan Shia Militancy (1979-2001)

- abuerfanparsi

- Oct 25, 2025

- 5 min read

The Fatemiyoun Division's origin story is not a simple one. It is deeply rooted in the Iranian Revolution, the U.S.-Soviet proxy war, and, most critically, Iran’s mobilization of Afghan mujahideen during the Iran-Iraq War. This history reveals a long-standing, complex strategy by the Islamic Republic to cultivate allied forces from Afghanistan's marginalized Shia Hazara community—a strategy forged in the crucible of 20th-century conflict.

I. The Roots of Mobilization: Hazara Marginalization and Early Networks

The relationship between Iran and Afghanistan’s Shia is built upon a foundation of shared faith and profound historical marginalization. For generations, Iran's holy cities of Mashhad and Qom have served as vital religious, cultural, and political centers for Afghanistan's ethnic Hazaras. Long persecuted by Afghanistan's Pashtun Sunni elite—including a history of enslavement in the 18th and 19th centuries and systemic discrimination well into the 20th—the Hazaras were firmly placed in the country’s underclass. Despite the official abolition of slavery in 1923, the rise of Pashtun nationalism, land dispossession, and political exclusion forced many into poverty, working as domestic servants or manual laborers.

This systemic persecution, as noted by scholar Amin Saikal, contributed to a "culture of exile" and a valorization of resistance within the community. Denied access to formal education for decades, many Hazaras turned to mosques and madrassahs, with the most ambitious seeking higher learning in the seminaries of Najaf, and crucially, Qom and Mashhad. This educational migration produced a cadre of educated Hazara elites, with Sayed Ismail Balkhi and Ayatollah Mohaqiq Kabuli emerging as the critical first nodes in a network linking Afghan Shia to Iran's power centers.

Sayed Ismail Balkhi: The ideological progenitor, Balkhi was a pioneer of political Islam. His journey—from studying in Mashhad and escaping anti-Reza Shah protests in 1935, to a 15-year prison term in Afghanistan for an anti-government putsch, and finally his pivotal 1967 pilgrimage—culminated in meetings with an exiled Ayatollah Khomeini in Najaf. Their discussions on revolution and resistance forged a personal bond that would later become a strategic channel.

Ayatollah Mohaqiq Kabuli: The more authoritative religious figure, Kabuli came of age post-slavery and spent time in exile in Syria and Najaf before settling in Qom. Together, Balkhi and Kabuli represented the intertwined ideological and religious strands that would define the movement.

II. The Revolutionary Spark: Exporting Velayat-e Faqih

The 1979 Iranian Revolution was a seismic event, making tangible the dream of a state based on velayat-e faqih (Guardianship of the Jurist). Its impact immediately reverberated in Afghanistan. In the Hazarajat region, the formation of the Shuray-e Ittefaq council marked the first time in generations that Hazaras were self-governed.

Tehran acted swiftly to consolidate this influence. Imam Khomeini dispatched at least twelve official representatives (wakil) to the Hazarajat throughout the 1980s. Their mission was dual: to collect funds and to preach a hardline, revolutionary stance against the Kabul regime. This institutional outreach, powerfully reinforced by the pre-existing personal bond between Khomeini and Balkhi, solidified the connection. Afghan adherents to Khomeini's doctrine, known as the Khat-e Imam (Imam’s Line), began organizing. Initially disorganized, they eventually sought religious edicts (fatwas) blessing jihad and formed factions with liaison offices in Tehran and Qom, which were later consolidated under the umbrella council Ettelaf-e Hashtgana (the Coalition of Eight).

III. The Crucible of War: Forging the First Proxy Militias

While the anti-Soviet jihad provided a cause, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) was the true furnace in which the prototype for the Fatemiyoun was forged. Saddam Hussein’s invasion, driven by territorial disputes in Khuzestan and alarm at Khomeini’s calls for revolution, presented an existential threat. Khomeini’s government framed the conflict as a "Sacred Defense," a modern-day Karbala where martyrdom purified the community and saved it from unjust rule.

This narrative required manpower, leading to the formal mobilization of Afghans. Iran’s strategy was managed through a sophisticated, dual-track system:

Administrative/Religious Channel: The Office of the Representative of the Supreme Leader for Afghanistan Affairs served as the main outreach for cultural and religious indoctrination, mediating between groups.

Military Channel: The IRGC's Liberation Movements Unit, under Sayed Mehdi Hashemi, initially oversaw operations abroad, including Afghanistan. After its dissolution in 1982 for disloyalty, the Islamic Movements Training Center under IRGC Intelligence took over. The expeditionary Ramezan Base (headquarters of Department 900, the Quds Force's predecessor) provided high-level command.

It was IRGC commander Mohammad-Javad Hakim Javadi who proposed creating a formal Afghan unit for the Iraqi front to better train them for the anti-Soviet jihad. Thus, the Abouzar Brigade was born, its name evoking the exiled companion of the Prophet, a poignant symbol for the marginalized Hazaras. Recruited from Afghan Islamist parties and integrated into Ramezan Base, the Brigade deployed to Kurdistan in the winter of 1985-86, with some fighters rotating between the fronts in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, the Brigade's story ended in failure and foreshadowed future problems. It disbanded after just a year, with official fatalities estimated at a staggering 2,000-3,000. It spoiled the chance for a permanent "Hezbollah" in Afghanistan, as the tactic bred deep resentment.

IV. Adaptation and Setbacks: From the Post-Soviet Vacuum to the Taliban

The post-Soviet era forced a recalibration of Iran's strategy. The formation of the mainstream Hazara party, Hizb-e Wahdat, in 1989, and its subsequent political compromises, led Tehran to adopt a more pragmatic, interest-based policy. This culminated in a dramatic shift in the early 1990s when Iran cut ties with Hizb-e Wahdat for opposing the Northern Alliance's Burhanuddin Rabbani, even encouraging non-Hazara Shia groups to split and join Rabbani's government. This "fickle" policy alienated many young Hazara leaders in Kabul.

The Taliban's rise in 1996 forced another abrupt pivot. Alarmed, Iran rejoined Russia and India in supporting the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance. This period saw the rise of Qasem Soleimani, who played an instrumental role in forming the "United Front" (Jabha-e Muttahed). Simultaneously, the Quds Force attempted to resurrect a loyal militia from the remnants of the Abouzar networks, creating Sepah-e Mohammad (Mohammad Corps). Trained in Zahedan, its goal was to destabilize the Taliban in western Afghanistan. However, attempts to foment rebellion in Herat city and district failed, and the force was deployed unsuccessfully to Sunni districts in Takhar and Farah before Soleimani dissolved it.

Despite these failures, this era was crucial. It cemented the Quds Force's operational role and, through its support to the Northern Alliance, helped Iran mend fences with disaffected Shia groups. Parallel to this, in Pakistan, the clerical networks of Arif al-Husayni—Khomeini's student and the "spiritual father of the Zeynabiyoun"—were established, creating a parallel structure for future mobilization.

Conclusion: A Blueprint Forged in Fire

The period from 1979 to 2001 provided the Islamic Republic the ideological appeal of velayat-e faqih and the "Sacred Defense" narrative for mobilizing the marginalized. The personal networks, veteran cadres, and strategic lessons—including the failed experiments of the Abouzar Brigade and Sepah-e Mohammad—remained dormant after the 2001 U.S. invasion. They formed a direct lineage, waiting to be reactivated in the next geopolitical shift, which would give rise to the Fatemiyoun Division as we know it today.

This article is written by Abu Dhar al-Bosni (lokiloptr154668 on X) and does not necessarily reflect the views of A.E.P. (the owner of the website), nor does it necessarily represent an agreement with these perspectives.

Comments